Haunting emblems: Tomasz Treter in Aleksandra Waliszewska’s interpretation

Can the modern reader, leafing through engravings in old prints, find something for herself? Surely, the popularity of increasingly numerous Facebook fan pages dedicated to sharing historical engravings of animals or drawings sketched by bored monks on the margins of manuscripts centuries ago, demonstrates that old pictures are as entertaining today as they were in their time. But can the figures and scenes from moralistic emblems, with their esoteric quality and the requirement of the readers’ ability to identify symbolic codes, haunt us in our dreams and nightmares?

Tomasz Treter (1547–1610) was a Polish priest and one of the most trusted associates of the cardinal and papal legate in Poland, Stanisław Hozjusz (Hosius), the official responsible for implementing the reforms of the Council of Trent and introducing the Society of Jesus to Poland. Besides working in Hosius’ office, Treter fulfilled his ambitions as an artist, writer and engraver. In Poland, he had no opportunities to become a professional engraver. Son of a bookbinder, Treter endeavored to acquire his desired skills during his diplomatic stay in Rome (1569–1584). His first work Theatrum virtutum was prepared soon after the death of Hosius in 1579[1].

The collection of emblems Symbolica vitae Christi meditatio (1612) is Treter’s last work, particularly interesting in the light of today’s fascination with historical imagery. Treter was the author of the emblematic compositions, but the engraver was his nephew, Błażej Treter. The book was published posthumously by Georg Schönfels. It contains 123 copperplate engravings. The main topic of the collection was the meditation of the symbols of the life of Christ. However, the presentation of the items in the icons exceeds Christian symbolism. Objects and figures connected with the life of Christ are extruded from reality and placed within compositions which bring surrealist visions to mind. They include: a pair of human eyes drifting in a vacuum (the symbol of the original sin), two winged hands (contemplatio), a male torso dangling from a tree branch with pouch hanging on its neck (Judas), hands emerging from behind a cloud and washed in a washbowl (Pontius Pilate), an hourglass hanging from a cloud (vigilantia), a heart with a mouth placed between two palms, one open and one closed (sinceritas), severed heads of infants lying on the ground and a hand lifted above them wielding sword (infanticidium) and many more.

Ideas for Treter’s imaginarium come from the Bible (especially the Psalms and Gospels) as well as the writings of Church Fathers (Gregory the Great and Hieronymus). Focusing on “sacred texts” is characteristic for this trend in emblematics, called “the sacred emblems” (emblemata sacra) by the one of the main figures of counterreformation, Antonio Possevino, in his most significant work Bibliotheca selecta. He advised artists to compose emblems in such a way that they depict God’s wisdom and become an impulse to “piety, virtues and nobility of the soul”[2]. According to Possevino, the topic of this type of emblems was supposed to rely on the Old and New Testament. By abandoning pagan themes, emblematics was meant to be a response and counterbalance to “indecent, secular painters”[3]. As a model example Possevino pointed to the emblem entitled Non quae super terram from Claude Paradin’s Devises heroïques (1557). The pictura shows hands extending from behind clouds and reaching for manna from heaven – the symbol of the Holy Sacrament[4]. Possevino’s model emblem is similar to Treter’s works in its minimalistic expression and the sparing selection of elements (a pair of hands and manna are canonical symbols from biblical stories). In fact, Treter modelled his designs on few of Paradin’s emblems. For example Paradin’s emblematic icon In sibilo aurae tenuis has been copied exactly in Laetitia spiritualis and the icon from the emblem Hoc Caesar me donavit was the model for Treter’s Desiderium coelesti.

According to the title of Treter’s book, the emblems were supposed to be used as a starting point for meditation on certain episodes from the life of Christ. They visualize historical events, because – as Treter asserts – Christ cannot be seen in any other way. Therefore, a Christian should meditate on some aspects of Christ’s earthly life. Such a construction of reader experience is similar to Louis Richeome’s project of emblematic-mnemonic figures. According to the French Jesuit, emblems could bring to mind the most important truths from the Bible as well as Catholic dogmas, while being very persuasive vehicles for the contemplation of the love of God and the necessity to reciprocate it[5]. For Treter, the contemplation of the life of Christ, for which his emblems were useful and effective, helps to expel sin from everyday life.

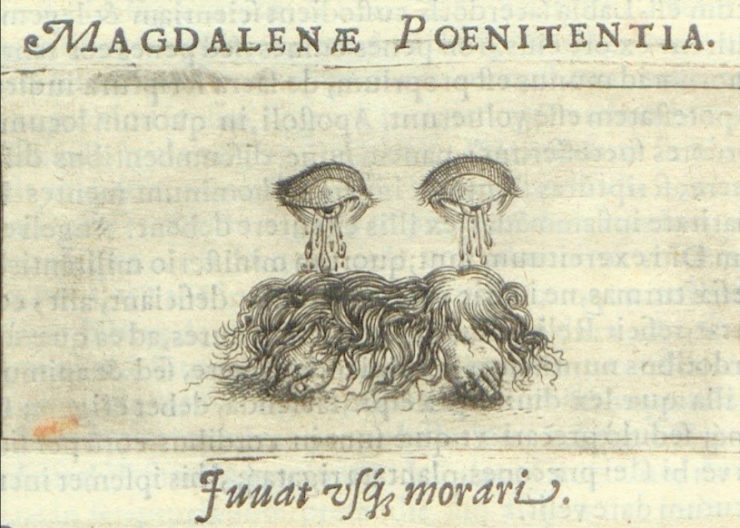

Despite the strong connection of Treter’s symbols with Christology, the Polish painter inspired by them, Aleksandra Waliszewska (b. 1971) stripped them from their original context by preparing new compositions on the basis of Treter’s graphic motifs. When looking at Treter’s work with fresh eyes, more attuned to twentieth-century art, its truly surrealist character can be detected – and Waliszewska makes use of this. For example, Treter combined detached body parts in his compositions, which continue to affect our emotions and memories even today. The emblem Magdalenae poenitentia (The Penance of Magdalene) depicts a pair of eyes crying tears onto two human feet covered by a clump of hair. A viewer acquainted with the Christian iconosphere immediately recognizes the meaning of such a juxtaposition: it refers to the washing of Christ’s feet with tears and oil by the “a (…) woman who lived a sinful life” (Luke 7,36–38), identified in the Christian tradition either as Mary (Martha’s sister) or Mary Magdalene.

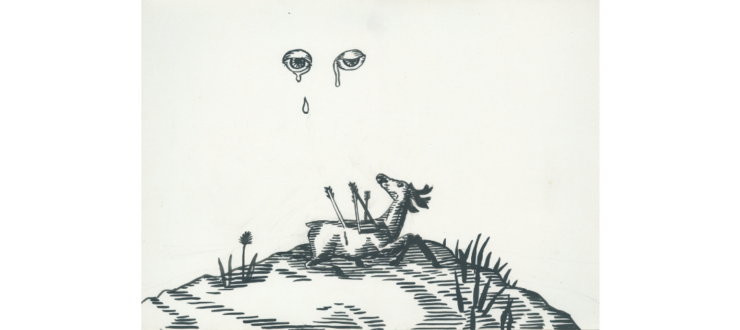

Aleksandra Waliszewska transfers the faceless eyes from the abstract space of Treter’s emblem into a landscape of a deeply distressing nightmare – the typical background of her paintings. Here, it is not the weeping penitent who grieves over his sinfulness while meeting with his Saviour, but the sky itself mourns a dying deer (Fig. 2) or centaur (Fig. 3) about to be caught by a hunter (as suggested by the arrows which have sunk deep into their bodies).

In Waliszewska’s gouaches, the cruelty of the last moments of Christ and the themes of Passion, turn into surrealistic scenes from a nightmare. Waliszewska retains the central composition and sparing use of artistic means characteristic of Treter’s emblems. Yet, her opening up the space in each painting deepens the emptiness of the world and the loneliness of the beings living in it. Now, the eyes looking from heaven do not necessarily belong to God overseeing his creation. In Waliszewska’s paintings, these eyes can reflect the sorrow and pain of a wounded animal, multiplicating its suffering and conveying its immersion in it.

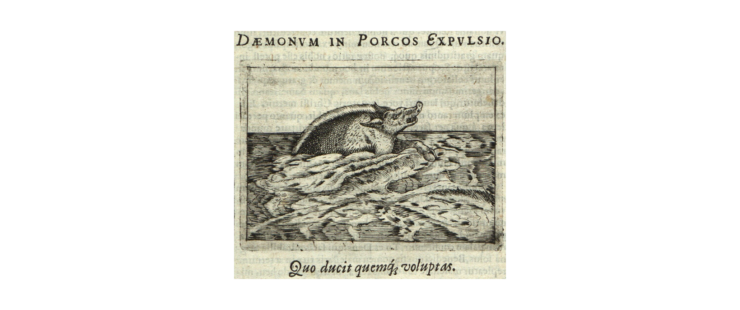

Exercises in Christian virtues were intended to prepare the faithful for a successful battle with the world, the flesh, and the devil. To the latter, Treter dedicated the emblem Daemonum in porcos expulsion, in which he illustrated the scene from Matthew 8,31–32. After Jesus landed on the shore of Gadarenes, he encountered two men possessed by demons, who lived in tombs nearby. The demons begged Jesus to expel them into a herd of pigs. Soon, the possessed herd rushed down into the lake and drowned in it. In the motto of the emblem (“Quo ducit quemque voluptas” [where pleasure leads everyone]) Treter cites De rerum natura of Lucretius (2,258)[6]. The fragment concerns the problem of human free will, which releases people from fate but also – as Treter suggests – can drive them to the baleful pursuit for the satisfaction of their desires.

The emblem became an inspiration for several of Waliszewska’s gouaches in which she portrays a certain kind of hermits devoid of any company, including the gaze of the Eye of Providence. Suffering and mad with fear, a panicked horse struggles for its life in an oceanic wasteland (Fig. 5). In a similar composition, another creature, a goat with empty eyes and lolled tongue, floats on the surface of the water (Fig. 6) It clearly symbolizes the devil. One more demonic creature depicted by Waliszewska is a mermaid which looks much more like a hunter than prey in its oceanic habitat. The monstrous creature is probably tracking her victim (who once caught will not be able to escape or expect mercy – as Waliszewska shows elsewhere, in her mermaid cycle). Both the centaur and the mermaid are partial self-portraits of the artist, who admitted to reproducing mostly her own features in order to avoid the stress of working with models[7]. The last painting corresponds with a biblical story: it shows a group of rodents which jump into the water as though in a swimming relay race and gather together among the waves.

Such an encounter of two artists four hundred years apart enables the viewer to deepen the perspective on both. Waliszewska has been fascinated with old Polish graphics for years. Besides Treter, to whom she dedicated an entire collection of paintings, another Polish engraver – Jan Ziarnko (1575–1630) – has also sparked her interest with his apocalyptic works. Waliszewska populates her gouaches with figures and motifs from old engravings, immersing them in traumatic and horrific spaces full of violence and fear. On the other hand, in his preparation of symbolic episodes for his own meditations upon the vita Christi, Treter tried to convince the reader that in a world without God’s guidance, there will be only sorrow and fear. While Treter wanted his emblems to fill the reader’s memory with episodes from the life of Christ and create an impulse to leading a moral life consistent with Christian values (Fig. 9), the same framework allowed Waliszewska to present a collection of scenes recalling the flashbacks from nightmares (Fig. 10). Who awakens from them can sigh with relief as though it was only a bad dream, but he or she will have these few scenes in mind for a long time.

For more Polish emblems visit the site of the Polish Emblem Project

Alicja Bielak

(Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, University of Warsaw)

Notes

* This paper is the result of a research project financed by state funds for science (2014–2018), under the auspices of the Diamentowy Grant program.

[1] G. Jurkowlaniec, Sprawczość Rycin. Rzymska twórczość Tomasza Tretera i jej europejskie oddziaływanie, Warszawa 2017, p. 248. See also T. Chrzanowski, Działalność artystyczna Tomasza Tretera, Warszawa 1984.

[2] A. Possevino, Bibliotheca selecta de ratione, ad disciplinas et ad salutem omnium gentium procurandam, Venetiis 1603, vol. 2, p. 551.

[3] Ibidem, p. 480.

[4] C. Paradin, Devises heroïques, Lyons 1557, p. 56: „La nourriture et aliment de l’Esprit, est le Pain celeste, ou saint Sacrement de l’Autel, designé par la Manne tombant des cieus des Israëlites, Mistere porté aujourdhui en Devise, par M. le R. Cardinal de Tournon”.

[5] L. Richeome, Tableaux sacres des figures mystiques du très auguste sacrifice et sacrement de l’Eucharistie, Paris 1609, p. [9]: „ces tableaux n’est pas mienne, ie n’y ay qu’un peu de langage: elle est du fils de Dieu qui iadus en a tire’ les lineamens et piur fils sur la membrance, ou de la loy de nature […] ou de son vieil Testament […]”.

[6] “Whence comes this free will for living things all over the earth, whence, I ask, is it wrested from fate, this will whereby we move forward, where pleasure leads each one of us, and swerve likewise in our motions neither at determined times nor in a determined direction of place, but just where our mind has carried us?” (Lucretius, On the nature of things, transl. C. Bailey, Oxford 1948, p. 74, v. 257–260).

[7] http://culture.pl/pl/tworca/aleksandra-waliszewska.