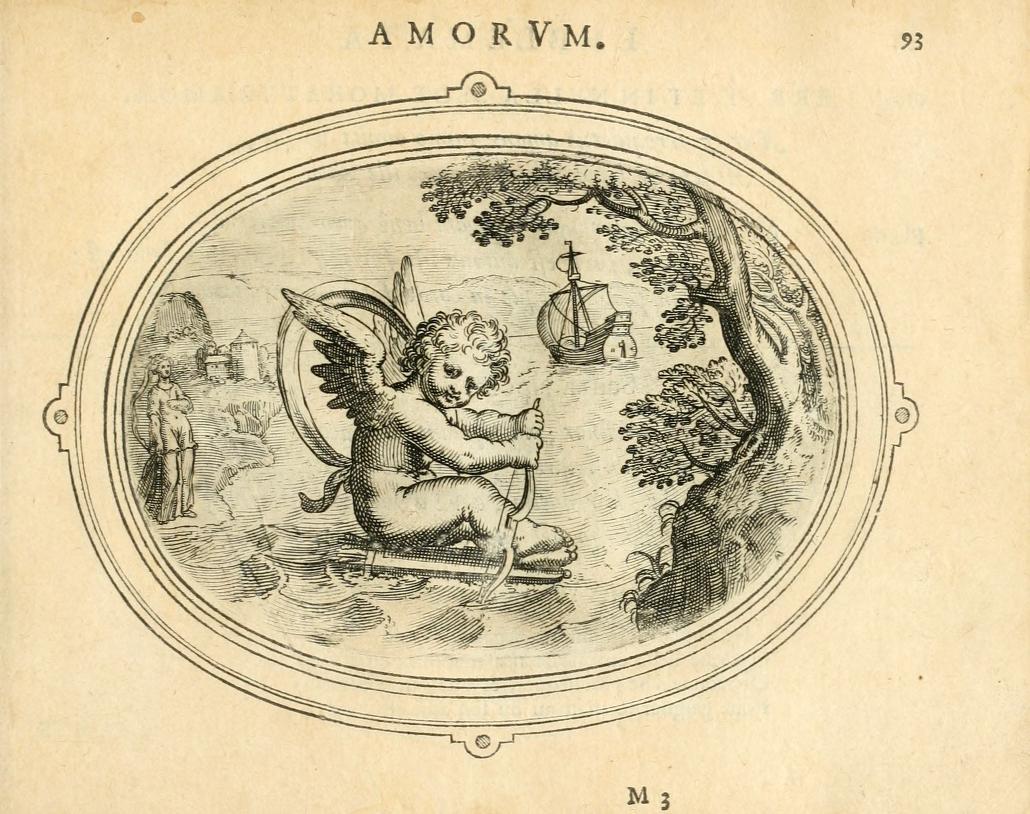

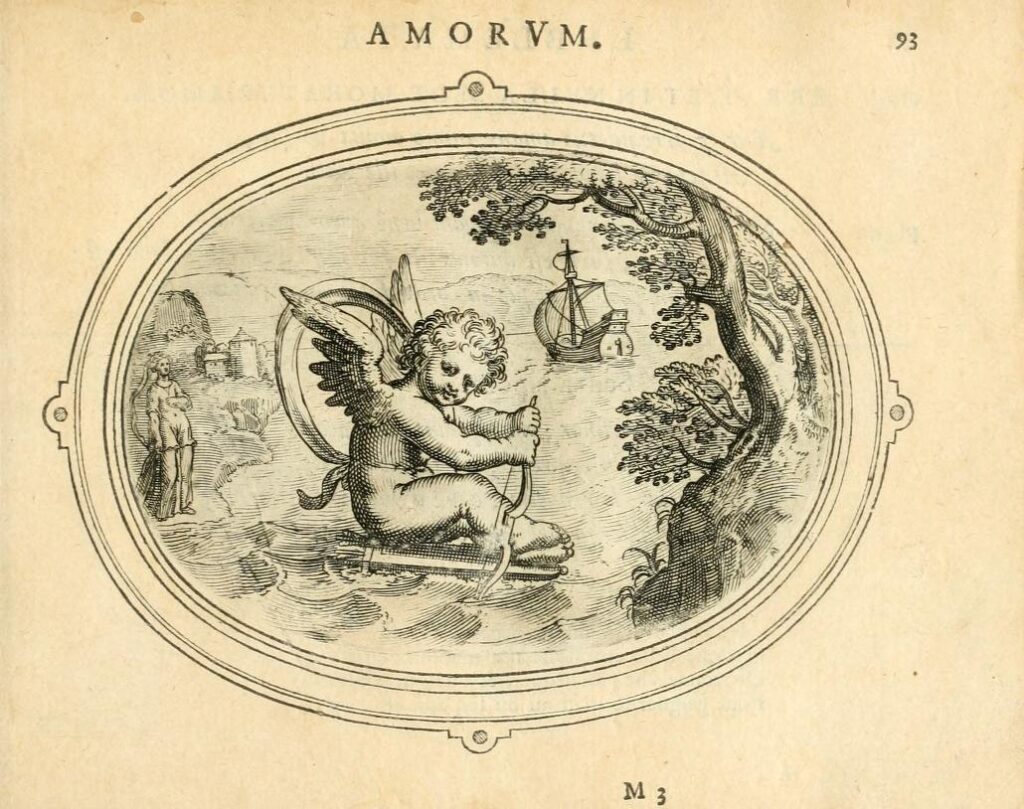

VIA NVLLA EST INVIA AMORI.

Quæ non tentet Amor perrumpere opaca viarum,

Qui infidi spernit cæca pericla maris?

Pro rate cui pharetra est, pro remo cui leuis arcus;

Vt portum obtineat, quidlibet audet Amor.

Love fyndeth meanes.Behold how Cupid heer to crosse the sea doth prooue,

His quiver is his bote, his bow hee makes his ore,

His winges serue for his sayles, and so love euermore

Leaves nothing to bee donne to come unto his loue.

Ben sa trouar la strada.Vedete il Dio d’Amor che solcar’ osa

Il profondo Ocean sul suo turcasso,

l’Arco serue di remo, e non è lasso,

Per veder la sua Dea, tenta ogni cosa.

Liefde vindt middel.Siet hoe Cupido vaert door baren/ en door stromen/

Sijn koker hem een schip/ sijn boogh een riem verstreckt/

Sijn slueyerken een seyl: als Liefd’ een minnaer weckt

Gheen middel hem ontbreeckt om by sijn Lief te comen.

Amour trouue moyen.Voycy le Dieu d’Amour, qui hardy passer ose

Les vagues de la mer, flottant sur son carquois,

d’Vne rame luy sert son petit arc Turquois.

l’Amant pour voir sa Dame entreprend toute chose.

(Otto Vaenius – Amorum emblemata (1608), Emblem 47)

Otto Vaenius’s emblem ‘Via nulla est invia amore’

In these troubled times, when many countries struggle with extremism, intolerance, and violence, I think love is an appropriate subject for SES’s Emblem of the Month. Through love emblems like this one, perhaps people and religions will find creative ways to reach across the wide ocean of their differences so that this basic virtue can unite humankind.

In issue number 30 of the SES Newsletter (January 2002), Simon McKeown writes an interesting research note about an emblematic lady’s watch from the late seventeenth century (c. 1690) from the London workshop of Nicholas Massy the Younger. The watch is in the Timepieces Collection in the Ashmolean Museum’s Department of Western Art (WA1947.191.98). Its case bears a tiny picture in a central roundel which the museum catalogue tentatively describes as “Cupid? on a raft at sea.”

McKeown traces the image’s origin to the emblem in Vaenius’s Amorum Emblemata whose inscriptio reads “Via Nvlla est in Via Amore.” McKeown describes the image as follows:

The pictura shows Amor using his quiver as a raft and his bow as an oar to cross a stream, where, on a far bank, his beloved awaits him. Amor is helped in his crossing by wind that catches his cloak, turning it into a sail. The maker of the watchcase has effected some slight changes in appropriating the emblem for his design. The Amor on the watch grips his cloak with his left hand, unlike the Amor in the emblem who uses both his hands for rowing; the Amor on the watch also faces in the opposite direction to the figure in the emblem. This may be because the case-maker based his motif on the reversed image in Raphael Custos’s adaptation of Vaenius’s book, the Emblemata Amoris Consecrata (Augsburg, 1622).

From this he deducts that “The strong amorous theme of the case, and the tiny proportions of the piece, make it likely that the watch was intended to be a love token between a suitor and his mistress.”

McKeown adds:

The emblem of Amor crossing a stream on his quiver is, as has been noted by Henkel and Schöne [col. 490], and later Karel Porteman [15], a humorous reworking of an earlier emblematic tradition found in Gilles Corrozet (and later appearing in Camerarius, Rollenhagen, Wither, Visscher and elsewhere) that depicted a squirrel crossing a river on a raft of twigs of bark. Corrozet in turn derived his motif from a tradition recorded in the natural histories, such as the representative accounts by Gesner and Olaus Magnus, who noted that squirrels crossed rivers and streams by sitting on natural rafts, guiding themselves over by the use of their tails as sails. […] Corrozet had extrapolated the moral that just as a squirrel applies its small store of intelligence to solve the difficulty of crossing streams, so mankind should use his natural ingenuity to master hazards and hindrances. In Vaenius’s appropriation of this emblem, he had wittily replaced the squirrel with Amor and fixed the objective of his voyage as his beloved waiting on the distant shore. The moral of the emblem now becomes that “loue euermore / Leaues nothing to bee donne to come vnto his loue.” Vaenius’s emblem therefore encourages the lover to show diligence, sedulity and invention in the pursuit of his mistress.

Notwithstanding Vaenius’s possible debt to Corrozet, he probably found a ready-made graphic transposition of the squirrel’s tradition in many more ancient images.

In fact, Santiago Sebastián López states in his book dedicated to the study of Dutch love emblems that he has found the graphic source of this particular emblem by Vaenius in an engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi (d. 1527) (p. 90). Raimondi’s engraving, with the motto “Sic fvga violenta monet,” has the structure of an impresa or device. It is identified on the websites of The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York, The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, The Ashmolean Museum, The Museum of Fine Arts of Budapest, and The Amica Library either as “Eros Escaping by Sea” or as “Eros escaping by sea, using his bow to propel a boat made from his quiver with an arrow as the mast and his blindfold as the sail.” These websites say it is after an engraving made around 1515-27 by Marco Dente da Ravenna (d. 1527) after a drawing by Raphael (d. 1520).

There is also a print by Agostino del Musi (known as Veneziano) called “Eros in the sea,” dated 1520-36, where the same image appears in between Venus standing on a seashell and a seated man sleeping. The seated man might be Palinurus, the helmsman of Aeneas’s ship, although the epigram below the image mentions Tiphys, the pilot of the Argo, and Jason. The epigram reads:

Cosi tal destreza Amor trapassa et arte

Del mar, ch’io spango il periglioso varco,

Del uelo fa le uele a l’aura sparte,

La barca è la faretra, Il remo è l’arco

Le corde del bell’arco son le sarte

L’arbore um stral di foco, et fele carco;

Cosi s’è fatto nel mio largo humore

Tiphi, et Jason senza maestro Amore.

For Mario Praz, it is possible that Vaenius derived this emblem from Scève. Sebastián quotes Praz, who qualified Vaenius’s emblem as:

Alexandrian caprice which had greatly attracted the French poets, such as Scève (Délie, diz. 94):

… Sa trousse print, et un fuiste l’arma:

De ses deux traictz deligemment rama,

De l’arc fit l’arbre, et son bandeau tendit

Aux ventz pour voile…Olivier de Magny (Soupirs, LIV):

I’ avoy fait de mes pleurs un fleuve spatieux

………………………………………

Il feit de son carquois une barque subtille,

Un, mast feit de son arc à navrer tant habille,

Et une voile feit du bandeau de ses yeux.

De la corde de l’arc des cordaiges Il feit,

Ses traits d’or et de plomb pour avirons il meit,

Et de mille soupirs Il feit enfler sa voile:

Et voyant la Maitresse à l’heure sur le bord,

Il invoqua son aide, et parvint à bon port,

Ayant son oeil divin pour Phare et pour estoille”

(Praz, p. 112).

The theme was exploited not only in Italy and France, but also in Spanish Siglo de Oro poetry. My reflections in this note were prompted by an anonymous gloss in the Cartapacio de Pedro de Peganos, a manuscript cancionero from the late sixteenth and early the seventeenth centuries, recently edited by J.J. Labrador and R.A. DiFranco (n. 321, p. 259, repeated in n. 379, p. 281, with slight spelling variants), which reads:

[PIE]

Pero con más quedo io.

GLOSA

Biéndose Amor en estremo

i que cassi se anegaba,

hizo varco de la aljaba,

del belo vela, y un remo

de una flecha que tiraba.

Del arco, mástil y entena,

Cuerda, de la que quitó,

y a bela y remo salió

con arto trabajo y pena,

pero con más quedo yo.

This gloss is not exclusive to Penagos. It also appears in the Cancionero de Pedro de Rojas, edited by the same scholars (Labrador and DiFranco) and María T. Cacho (n. 178, p. 253), and in MS 22.852 of the National Library of Spain (p. 2).

Rubem Amaral Jr.

(Independent researcher)

Bibliography:

- Cancionero de Pedro de Rojas, Prólogo de José Manuel Blecua, Edición de J.J. Labrador Herraiz, Ralph A. DiFranco, María T. Cacho, Cleveland: Cleveland

State University, 1988 (Col. Cancionerros Castellanos, 1). - Cartapacio de Pedro de Penagos (Real Biblioteca de Madrid, II-1581), Prólogo de Antonio Carreira, Estudio de Abraham Madroñal, Edición de José J. Labrador Herraiz, Ralph A. DiFranco, Moalde: 2005 (Col. Cancioneros Castellanos, 8).

- McKeown, Simon: ‘An Emblematic Watchcase in Oxford’, SES Newsletter, Number 30, January 2002, pp. 6-11.

- Praz, Mario: Studies in Seventeenth Century Imagery, 2nd ed., Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 1964 (Sussidi Eruditi, 16).

- Sebastián López, Santiago: La mejor emblemática Amorosa del Barroco. Heinsius, Vaenius y Hoof, Ferrol (A Coruña): Sociedad de Cultura Valle Inclán 2001 (Col. SIELAE).

Online Sources:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Collection Online (link to item)

- Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaelogy, Oxford, Western Art Prints Collection (link to item 1 | Llink to item 2)

- Fine arts museum of San Francisco, de Young l Legion of Honor (link to item)

- Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Italian and French Prints before 1620, Zoltan Kárpati and Eszter Seres (link to item)

- The AMICA Library (link to item)